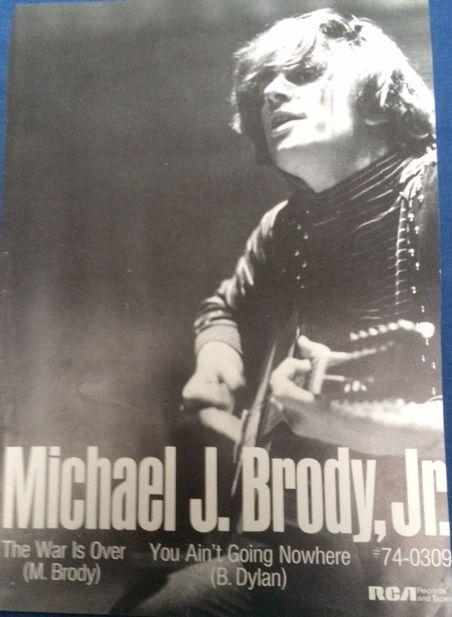

The story of Michael J. Brody Jr. has been gnawing at me since January 1970. I lived through his giveaway, and marveled at how his fortune seemed to climb each day in the press.

As the United States became bogged down in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars in 2007, my thoughts more and more drifted to the quagmire of Vietnam, and to Brody, who had tried to end the Vietnam War by showing its absurdity. Within a week, just by doling out some cash, promising more, and bouncing a couple of dozen checks, he went from nobody to a rock star to an anti-War protestor demanding to see Nixon to discuss the terms of his peace plan—a plan cunningly simple in pure American capitalist terms.

I started this project in late 2007 because I wanted to make sense of Brody, his giveaway and his Vietnam War plan. Was he victim or victimizer or both? Did he believe the outlandish statements he made? Was he high or insane or a clever political prankster? And I also wondered what had become of him between the giveaway and his death. I thought I might find the answers to these and other questions. Above all, I wanted to make a factually accurate account of his time in the public eye, from giveaway to death. As I quickly discovered, making sense of Brody and his life is difficult. He can be easily dismissed—and has been by many—but I think that that is unfair.

My journey searching for the truth of Michael J. Brody Jr. has led me many places—to various libraries, to Scarsdale, to the Nixon Archives, to the FBI and Secret Service files, to a storage room of a church outside Woodstock. It’s been a long strange trip, for certain. I’ve learned a lot about oleomargarine, and its bizarre history, and I’ve learned much about Ed Sullivan, Walter Winchell, the Café Society, the packaging of news stories by the press, and, of course, Vietnam. I’ve learned more about the Jelke family than the Jelkes probably know. I’ve met some great people along the way who assisted me in this very personal quest. Out of respect for their privacy, I will not mention their names. I thank them, nevertheless. They know who they are.

The website has three related stories: The Oleomargarine Heir, Another Oleo Heir, and The Oleo Fortune. Please enjoy.