“Insane in a beautiful way.”

At first, when Brody repeatedly said that his giveaway was designed to make up for the harm that millionaires had caused, the press scurried for comparisons, many finding analogies in popular culture. Some reporters were reminded of John Beresford Tipton in The Millionaire, the late 1950s television show that was being re-run on local New York stations. Each 30-minute show began with Tipton giving his charge, Michael Anthony, a $1,000,000 check to bestow upon an unsuspecting recipient. The show then detailed the trials and tribulations of the recipient. For others, Brody’s spending spree conjured Monty Brewster in Brewster’s Millions, the 1903 novel that had been made several times into a movie, the most recent appearing in 1945. Pursuant to his uncle’s will, Brewster had to spend a large inheritance (about $1,000,000) in a short time in order to receive another, larger inheritance. For the more literary minded, Brody was reminiscent of Eliot Rosewater in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1965 novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. The trustee of his family’s sizeable foundation, Rosewater attempts to bestow good will upon the citizens of a small mid-western town. Relatives and lawyers eventually have him committed.

At first, when Brody repeatedly said that his giveaway was designed to make up for the harm that millionaires had caused, the press scurried for comparisons, many finding analogies in popular culture. Some reporters were reminded of John Beresford Tipton in The Millionaire, the late 1950s television show that was being re-run on local New York stations. Each 30-minute show began with Tipton giving his charge, Michael Anthony, a $1,000,000 check to bestow upon an unsuspecting recipient. The show then detailed the trials and tribulations of the recipient. For others, Brody’s spending spree conjured Monty Brewster in Brewster’s Millions, the 1903 novel that had been made several times into a movie, the most recent appearing in 1945. Pursuant to his uncle’s will, Brewster had to spend a large inheritance (about $1,000,000) in a short time in order to receive another, larger inheritance. For the more literary minded, Brody was reminiscent of Eliot Rosewater in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1965 novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. The trustee of his family’s sizeable foundation, Rosewater attempts to bestow good will upon the citizens of a small mid-western town. Relatives and lawyers eventually have him committed.

None of these comparisons was a perfect fit, however. Brody’s generosity was not as clandestine as Tipton’s. Nor was Brody’s giveaway comparable to Brewster’s spending spree, which was motivated by greed. Brewster was forbidden by the terms of his uncle’s will from giving his money away. He had to spend it in order to obtain a larger fortune. More apropos was the comparison between Brody and Vonnegut’s character, as each sought to unyoke himself from a family fortune. Brody’s giveaway promise completed the arc of the American Dream—from his great-great-grandfather, the German büttner who immigrated to America for a better life; to his great-grandfather, the margarine entrepreneur who flirted with the law as he fought the color wars; to his grandfather, the successful businessman who sold the family business for a fortune; to his wastrel uncles who dissipated much of the fortune while living the life of leisure; to himself, the hippie philanthropist who saw a way to help others with the monies his ancestors had earned and placed in trust for their progeny.

None of these comparisons was a perfect fit, however. Brody’s generosity was not as clandestine as Tipton’s. Nor was Brody’s giveaway comparable to Brewster’s spending spree, which was motivated by greed. Brewster was forbidden by the terms of his uncle’s will from giving his money away. He had to spend it in order to obtain a larger fortune. More apropos was the comparison between Brody and Vonnegut’s character, as each sought to unyoke himself from a family fortune. Brody’s giveaway promise completed the arc of the American Dream—from his great-great-grandfather, the German büttner who immigrated to America for a better life; to his great-grandfather, the margarine entrepreneur who flirted with the law as he fought the color wars; to his grandfather, the successful businessman who sold the family business for a fortune; to his wastrel uncles who dissipated much of the fortune while living the life of leisure; to himself, the hippie philanthropist who saw a way to help others with the monies his ancestors had earned and placed in trust for their progeny.

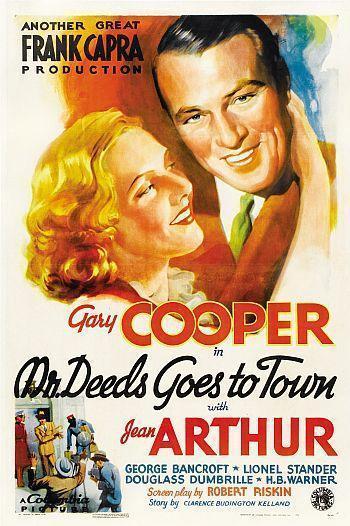

Perhaps the most obvious analogue, however, had escaped observation. In its lineup for the 1969-70 television season, CBS offered Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Although the series was cancelled mid-season, it was still playing when Brody hit town. Frank Capra’s 1936 film of the same name had achieved more success. It was nominated for five academy awards, including best picture, best director, best screen play and best actor. Capra won for best director. In the film, Gary Cooper played Longfellow Deeds, from Mandrake Falls, Vermont. Deeds was a seemingly simple man who wrote poems for post cards, ran a tallow works, and played the tuba in his town’s band. The film posed a simple question: Would a sane man give away millions? That question had real poignancy during the Depression, when the unemployment rate was 25 percent in 1933 and 17 percent in the year of the film’s release.

The film opens with the death of Deeds’ uncle in a car crash. The uncle’s will names Deeds the beneficiary of a fortune worth at least $20,000,000. When told of his inheritance, Deeds questions why his uncle left him the money. “I don’t need it,” he says. Out of a sense of family obligation, Deeds heads to New York City to claim his inheritance and tend to his uncle’s estate and business interests. In New York, Deeds becomes a media sensation. Various moochers, money grubbers, and claimants besiege Deeds with requests and demands. After a late night encounter with a truly desperate man—a destitute, starving farmer—Deeds decides to give his fortune away. The papers headline his sensational plan but the estate’s lawyer and distant family members attempt to have Deeds declared mentally incompetent. The newspapers clamor to cover the trial, where Deeds must prove that a man who would give his fortune away is not necessarily insane. At the trial, the estate’s lawyer produces evidence that Deeds has taken leave of his senses, including testimony from two sisters from Mandrake Falls who say that he is “pixilated.” Deeds reluctantly defends himself, refuting each accusation except one. “You haven’t yet touched upon the most important point,” the Judge responds. “This rather fantastic idea of yours to want to give away your entire fortune is, to say the least, most uncommon.”

Like Deeds, Brody had come upon the same “uncommon” and “fantastic” idea. The movie may have played a role: it was one of Brody’s favorites. As soon as Brody announced his intention to give his fortune away, papers immediately started questioning his sanity, albeit in a playful way. He was depicted as “madcap,” “eccentric,” or “whimsical.” One paper described him as “puzzling” and another as “mercurial.” The term used about Longfellow Deeds—”pixilated”—would also have been appropriate. As explained to the judge in the movie by a psychiatrist, “pixilated” was “an early American expression derived from the word ‘pixies’ meaning ‘elves.’” According to the psychiatrist, early Americans “would say ‘the pixies got him’ as we nowadays would say ‘a man is balmy.’” No one truly questioned Brody’s mental health. For the press, his was a good story that had gotten better. Life was imitating art but with a modern twist. Instead of the owner of a tallow works who played the tuba in the town’s band, the press had an heir to a margarine fortune—a hippie and a songwriting one to boot.

Like Deeds, Brody had come upon the same “uncommon” and “fantastic” idea. The movie may have played a role: it was one of Brody’s favorites. As soon as Brody announced his intention to give his fortune away, papers immediately started questioning his sanity, albeit in a playful way. He was depicted as “madcap,” “eccentric,” or “whimsical.” One paper described him as “puzzling” and another as “mercurial.” The term used about Longfellow Deeds—”pixilated”—would also have been appropriate. As explained to the judge in the movie by a psychiatrist, “pixilated” was “an early American expression derived from the word ‘pixies’ meaning ‘elves.’” According to the psychiatrist, early Americans “would say ‘the pixies got him’ as we nowadays would say ‘a man is balmy.’” No one truly questioned Brody’s mental health. For the press, his was a good story that had gotten better. Life was imitating art but with a modern twist. Instead of the owner of a tallow works who played the tuba in the town’s band, the press had an heir to a margarine fortune—a hippie and a songwriting one to boot.

The debate about Brody’s sanity became more pointed after he announced his Vietnam Peace Plan. One newspaper reporter stated: “After reading and seeing (on TV) Oleo heir Mike Brody I think the boy needs a little help. He might have all that money but I don’t think he’s quite right.” Other papers started using harsher terms to describe him. He was no longer the giveaway heir or the hippie millionaire. Instead of “mad cap” or “whimsical” or “mercurial,” he was a “nut,” “kooky,” “flaky,” “strange, strange.” One paper, from a dairy state, joked that Brody’s craziness might be the result of eating oleomargarine. One writer said he would leave it to the experts to decide Brody’s mental stability or instability. Another paper thought that Brody was “either crazy or on the drug kick.”

Some reporters had tracked down Brody’s paternal grandparents, both Czechoslovakian immigrants in their 70s living in Duquesne, near Pittsburgh. Michael John Brody was called Big Mike. He had worked 40 years in the Pittsburgh steel mills before retiring nine years earlier. He and his wife were living on a meager pension—about $200 per month. They were not close to their grandson, and had not seen him in over 15 years. They last spoke to him, on the telephone, about three or four Christmases ago. They thought of him often, however, and wondered how he was. They usually mailed him a Christmas gift. A month before, they had sent him a scarf. They didn’t understand what their grandson was doing. Big Mike had had a stroke a few years earlier. He let his wife speak to the press. She had a heavy accent. “Something is wrong with him,” she told the reporters.

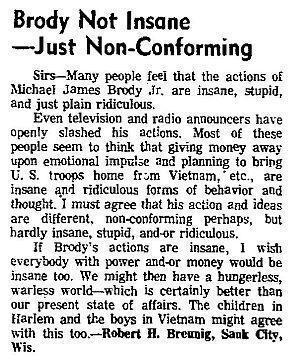

For many, however, Brody was “either crazy or the greatest publicity man around.” Even Renée’s mother thought that the giveaway had been nothing more than a publicity stunt. Time magazine posed it as a choice between whether Brody was “freakily foxy” or “foxily freaky.” Others saw Brody was an example of the kindness in the human spirit. One national religious leader said Brody was “an idealist who sincerely meant to do only good with the money he had at his disposal.” Some members of the public were also sympathetic. Brody’s message of peace and love had not been totally lost. A reader defended Brody in a letter to the editor of the Wisconsin State Journal. “Many people feel that the actions of Michael James Brody Jr. are insane, stupid, and just plain ridiculous,” the letter began. “If Brody’s actions are insane, I wish everyone with power and-or money would be insane too. We might then have a hungerless, warless world—which is certainly better than our present state of affairs. The children in Harlem and the boys in Vietnam might agree with this too.” Renée agreed. When she was asked about Michael’s sanity, she said. “If he’s insane, he’s insane in a beautiful way.”

For many, however, Brody was “either crazy or the greatest publicity man around.” Even Renée’s mother thought that the giveaway had been nothing more than a publicity stunt. Time magazine posed it as a choice between whether Brody was “freakily foxy” or “foxily freaky.” Others saw Brody was an example of the kindness in the human spirit. One national religious leader said Brody was “an idealist who sincerely meant to do only good with the money he had at his disposal.” Some members of the public were also sympathetic. Brody’s message of peace and love had not been totally lost. A reader defended Brody in a letter to the editor of the Wisconsin State Journal. “Many people feel that the actions of Michael James Brody Jr. are insane, stupid, and just plain ridiculous,” the letter began. “If Brody’s actions are insane, I wish everyone with power and-or money would be insane too. We might then have a hungerless, warless world—which is certainly better than our present state of affairs. The children in Harlem and the boys in Vietnam might agree with this too.” Renée agreed. When she was asked about Michael’s sanity, she said. “If he’s insane, he’s insane in a beautiful way.”