•••

An Age of Anarchy

On Thursday, April 30, 1970, President Nixon addressed the nation in a prime-time television speech. “Good evening my fellow Americans,” he began. He explained that, although he had announced a troop withdrawal ten days earlier, he had just ordered the invasion of Cambodia, a neutral country that bordered Vietnam. He told the viewing public that, at that very moment, American troops were crossing the border into Cambodia supported by American air power. Nixon stood by a map of Southeast Asia, pointing to the guerrilla camps just over the border in Cambodia that were being used as staging points for attacks on South Vietnam. America needed to escalate the Vietnam War in order to shorten it, he explained. If the guerrilla camps were not eliminated, South Vietnam would be “completely outflanked” and both South Vietnamese and American troops would be in “an untenable military position.” But, more important, the action was needed to protect the free world. “We live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home,” Nixon said. “We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States great universities are being systemically destroyed. Small nations all over the world find themselves under attack from within and from without.” But in that age of anarchy, the United States had to stay firm. “If when the chips are down the world’s most powerful nation—the United States of America—acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.” Nixon reminded the country that, during his campaign for the presidency, he had promised to secure a just peace. “I shall keep that promise,” he assured the country. He closed the speech by asking that the nation support “our brave men fighting around the world, not for territory, not for glory but so that their younger brothers and their sons and your sons can have a chance to grow up in a world of peace and freedom, and justice.”

On Thursday, April 30, 1970, President Nixon addressed the nation in a prime-time television speech. “Good evening my fellow Americans,” he began. He explained that, although he had announced a troop withdrawal ten days earlier, he had just ordered the invasion of Cambodia, a neutral country that bordered Vietnam. He told the viewing public that, at that very moment, American troops were crossing the border into Cambodia supported by American air power. Nixon stood by a map of Southeast Asia, pointing to the guerrilla camps just over the border in Cambodia that were being used as staging points for attacks on South Vietnam. America needed to escalate the Vietnam War in order to shorten it, he explained. If the guerrilla camps were not eliminated, South Vietnam would be “completely outflanked” and both South Vietnamese and American troops would be in “an untenable military position.” But, more important, the action was needed to protect the free world. “We live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home,” Nixon said. “We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States great universities are being systemically destroyed. Small nations all over the world find themselves under attack from within and from without.” But in that age of anarchy, the United States had to stay firm. “If when the chips are down the world’s most powerful nation—the United States of America—acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.” Nixon reminded the country that, during his campaign for the presidency, he had promised to secure a just peace. “I shall keep that promise,” he assured the country. He closed the speech by asking that the nation support “our brave men fighting around the world, not for territory, not for glory but so that their younger brothers and their sons and your sons can have a chance to grow up in a world of peace and freedom, and justice.”

Campus unrest started immediately. Students at the University of Maryland College Park ransacked the ROTC building, and the Maryland Governor put two National Guard units on alert. The Princeton student body voted to go on a general strike, as did students at the University of Pennsylvania and Rutgers. Stanford students also voted to strike at a rally held to protest Nixon’s decision, but the rally soon evolved into a rock throwing melee that was broken up by police using teargas. Over a thousand students from the University of Cincinnati marched from their campus into a downtown intersection, where they staged a 90-minute sit-in. The police made over 145 arrests when trying to disperse the crowd, which had effectively stopped all traffic. Student strikes, meetings and protests swept the nation. Protestors called for the Senate to censure Nixon. Others called for Nixon’s impeachment. Nixon was not swayed. He told a group of employees at the Pentagon that the students were “bums.” “You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses. Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world, going to the greatest universities, and here they are burning up the books, storming around about this issue. You name it. Get rid of the war there will be another one.”

Tension continued to build across the country over the weekend. Protests were staged on one campus after another. In Ohio, at Kent State University, anger from a Friday afternoon protest on campus spread to the business district of the City of Kent later that night, with students and others throwing bottles at passing police cars. Storefronts on North Water Street were shattered with rocks. A bonfire was set. The next morning the mayor of Kent declared a civil emergency and asked for assistance from the governor, who mustered the National Guard to keep order. By the time the Guard arrived later that evening, the ROTC building on the campus was burning. Hundreds of students stood around and cheered. Fire fighters were hit with rocks and broken bottles as they attempted to suppress the flames. Campus police in riot gear dispersed the crowd with tear gas. Tensions simmered Sunday as the students planned a rally for noon on Monday, May 4, on the grassy common area of the campus.

Fifteen minutes before the scheduled noon rally, the National Guard locked and loaded their M-1 rifles. The Guardsmen, most the same age as the protestors, formed a skirmish line. They fired tear gas canisters and began marching across the green lawn toward the protestors. Rocks and bottles were thrown by the students, who numbered around 800. Many more students stood off to the side watching the events. The troops marched across the commons, turned and started back. Around 12:25 p.m., when the troops reached Blanket Hill, a grassy knoll on the commons, some of the Guardsmen heard what they thought was a shot. Twenty-eight Guardsmen turned and opened fire on the crowd. The volley lasted 13 seconds. Sixty-one shots were fired. Four students were killed. Nine others were wounded. The nation reacted with horror. A general nationwide student strike was called, and a larger anti-war protest was scheduled for May 9 in Washington, D.C. One-hundred thousand students began descending on the capital. In New York, Mayor John Lindsay ordered all flags on city buildings flown at half-mast in memory of the Kent State martyrs and in support of the anti-war protestors. His show of sympathy was not well received by more conservative forces, which started calling him a commie rat or a traitor. Particularly incensed was the head of the Building and Trades Council of Greater New York, who was an outspoken supporter of Nixon’s war policy.

Fifteen minutes before the scheduled noon rally, the National Guard locked and loaded their M-1 rifles. The Guardsmen, most the same age as the protestors, formed a skirmish line. They fired tear gas canisters and began marching across the green lawn toward the protestors. Rocks and bottles were thrown by the students, who numbered around 800. Many more students stood off to the side watching the events. The troops marched across the commons, turned and started back. Around 12:25 p.m., when the troops reached Blanket Hill, a grassy knoll on the commons, some of the Guardsmen heard what they thought was a shot. Twenty-eight Guardsmen turned and opened fire on the crowd. The volley lasted 13 seconds. Sixty-one shots were fired. Four students were killed. Nine others were wounded. The nation reacted with horror. A general nationwide student strike was called, and a larger anti-war protest was scheduled for May 9 in Washington, D.C. One-hundred thousand students began descending on the capital. In New York, Mayor John Lindsay ordered all flags on city buildings flown at half-mast in memory of the Kent State martyrs and in support of the anti-war protestors. His show of sympathy was not well received by more conservative forces, which started calling him a commie rat or a traitor. Particularly incensed was the head of the Building and Trades Council of Greater New York, who was an outspoken supporter of Nixon’s war policy.

On May 8, about 1,000 college and high school students from New York marched on Wall Street to protest the Kent State Shootings, the invasion of Cambodia and the continuation of the Vietnam War. As the marchers chanted against the war in front of Federal Hall, a group of about 200 construction workers in hard hats descended upon them from all directions, determined to kick some hippie ass. The construction workers waded through the crowd, punching and kicking the protestors. Many protestors immediately sat down—the typical passive resistance reaction. They were pummeled as they sat. Police responded half-heartedly and let the carnage ensue. The next day, Mayor Lindsay openly criticized the police for the lack of an adequate response. President Nixon held an emergency press conference in an attempt to diffuse the tensions in the capital. Construction workers in New York planned their own march for the following week, in support of the war and against Lindsay.

While the nation unraveled, Brody holed up in his father’s Manhattan apartment. He had been brought back to New York, under medication. Renée had also come back east, but she had gone to her parents’ house in Ashokan. Brody and Renée spoke everyday by telephone. He talked of her pregnancy, of their future child. He was certain it would be a boy. He would name it after him. He took the anti-psychotic medication given him in California for a few days but stopped. He spent his days alone in the apartment, rolling and smoking joints. He had lost weight over the last several weeks, and his face was drawn and thin. He fretted about Nixon, but he could not join the protests: he was afraid of crowds and feared that he would be assassinated if he left the apartment. Without the anti-psychotic medication, he started to hear the voices again and could feel the hands upon him. They were out to get him, to maul and claw him to death. He spent days without bathing or changing his clothes. At other times, he refused to get dressed and wandered naked around his father’s apartment. He played albums on his stereo and strummed the guitar. He sorted leaf from stem and seeds. He got high.

May 11 was a sunny New York Monday. Brody was agitated. He lit the joint and took a few long drags. He sat in the chair and turned on the stereo, loud. He locked the door to the apartment and latched the security chain. He peered out the window and spied two or three persons on the sidewalk below. He raised the window in his father’s apartment and shouted to those below to move on. “I have no money. I have nothing,” he said. He closed the window and walked from room to room. He was alone. He was naked. He thought about calling the police for protection, but decided against it. He peered out the window again but the group of pedestrians was still there. He opened the window and yelled. “Get the fuck away. I have nothing.” He found about fifty dollars in small bills and change, and threw the fistful of money to the crowd. “You want something. Here is all I got.” He picked up an ashtray and threw it out the window. He threw pillows from the sofa, then some books, then his shoes. As he threw items from the window, the crowd below cheered and yelled “More.”

A neighbor soon called the police, and patrolmen Alfred Smith and Joseph Doherty from the East 67th Street Station arrived around 5:00 p.m. The crowd had increased to over 50, many of whom did not know it was Brody: they just knew that some naked man had thrown money from his window. Several hundred dollars, one in the crowd said. Maybe more, another reported, perhaps $1000. The patrolmen went directly to Brody’s father’s sixth-floor apartment. Brody let them in, complaining that he needed protection and that there were plots against him. He had gotten dressed and was happy to see them. He introduced himself by his full name and shook each man’s hand. An officer could smell the marijuana smoke in the apartment, and Brody was holding the remnants of a joint. The police looked at the roach.

“Have you been smoking marijuana?” Patrolman Smith asked.

“Yep,” Brody said. He offered the officers the roach. “You want some?”

“Got any more of that?”

“Sure do.” Brody walked barefoot across the lush wall-to-wall carpet to his room, returning a few seconds later with a half-pound of marijuana in a plastic bag and some rolling papers. The officers looked at the weed, then at Brody, then at each other. They then arrested Brody for felony possession. Brody insisted on getting his guitar and a floppy hat, and the officers obliged, for reasons that were not entirely clear to them. It was not standard operating procedure but the entire call had been non-standard.

Brody was booked, hat, guitar and all, taken to night court and released several hours later. The press waited.

“I’m just going to live the quiet life,” he told the reporters. “I’m going to dress up, be clean and be like a human being. I’m very sorry about all this, sorry I did these things. From now on, I’m going to be as quiet as a mouse. I’m really going to make a try at helping the world.”

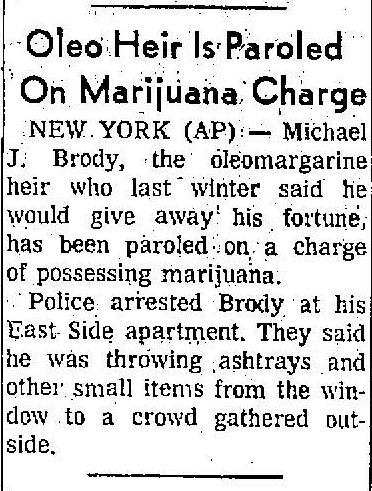

Brody’s arrest was carried by the New York tabloids but as a secondary story, a dozen pages deep. Nationwide, a scattering of papers carried AP or UPI stories—short ones, also buried far from the headlines. Brody was old news, which in the newspaper world meant he was no longer news. The world had moved on to other stories. The anti-war protests across the country continued. The massacre at Kent State was followed by another, at Jackson State in Mississippi on May 14, when seventy-five local and state police officers armed with shotguns, pistols, carbines and submachine guns opened fire on a group of students. Thirty seconds and more than 500 bullets later, two lay dead with a dozen others wounded. The trial against Charlie Manson and his followers was heading for opening arguments in June. Because Manson believed that the murders were directed by divine forces through the Beatles’ lyrics, the members of his “Family” had been sending letters and telegrams to Lennon and McCartney, urging them to come to Los Angeles for the trial. There was a rumor that Manson wanted to call Lennon as a witness to testify about the meaning of the songs on the White Album. The court martial of Lt. Calley for his role in the My Lai Massacre was scheduled to begin in May but was postponed to the late summer. As the reality of the proceeding loomed, a public debate emerged. For many, Calley was a war criminal, like the Nazis convicted at Nuremberg. For others, he was either a military man fighting a war where everyone was the enemy or a victim of the moral dilemma of the Vietnam War, if not all wars.

Brody’s arrest was carried by the New York tabloids but as a secondary story, a dozen pages deep. Nationwide, a scattering of papers carried AP or UPI stories—short ones, also buried far from the headlines. Brody was old news, which in the newspaper world meant he was no longer news. The world had moved on to other stories. The anti-war protests across the country continued. The massacre at Kent State was followed by another, at Jackson State in Mississippi on May 14, when seventy-five local and state police officers armed with shotguns, pistols, carbines and submachine guns opened fire on a group of students. Thirty seconds and more than 500 bullets later, two lay dead with a dozen others wounded. The trial against Charlie Manson and his followers was heading for opening arguments in June. Because Manson believed that the murders were directed by divine forces through the Beatles’ lyrics, the members of his “Family” had been sending letters and telegrams to Lennon and McCartney, urging them to come to Los Angeles for the trial. There was a rumor that Manson wanted to call Lennon as a witness to testify about the meaning of the songs on the White Album. The court martial of Lt. Calley for his role in the My Lai Massacre was scheduled to begin in May but was postponed to the late summer. As the reality of the proceeding loomed, a public debate emerged. For many, Calley was a war criminal, like the Nazis convicted at Nuremberg. For others, he was either a military man fighting a war where everyone was the enemy or a victim of the moral dilemma of the Vietnam War, if not all wars.

The story of Brody’s arrest was buried deep enough that it had escaped the attention of many. One sports writer, for instance, mused in his column about Brody’s whereabouts on May 23, 1970: “Whatever happened to Michael Brody, the man who was giving all that money away?” Another writer responded to a reader’s inquiry about Brody’s whereabouts by indicating that Brody “had hopped out of sight after flashing across the headlines and TV screens giving away money like it was facial tissue.” The writer added that the last he heard, Brody “was still trying to get his accounts settled.”

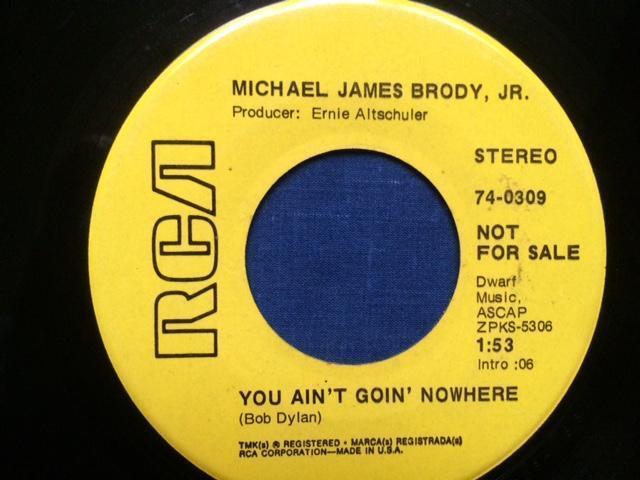

The metaphor of tossing away facial tissue surfaced again in the summer. David Reitman’s article appeared in the July 6, 1970, edition of Rock, a short-lived newspaper dedicated to the music industry. Reitman had attended Brody’s recording session at RCA’s Manhattan studio in January. He wrote his story soon thereafter but it was not published until the summer, after Brodymania had died. Brody had been universally described by the media as a hippie from the moment he landed at JFK Airport in his chartered 707. When the giveaway crumbled, editorialists dismissed Brody as a drugged-out, peace loving hippie—a symbol of what was wrong with the youth of America. Reitman had a different view: Brody was not a hippie, Reitman argued. The hippie movement had been born in 1966 and died after the Summer of Love in 1967. Woodstock, the festival, was after thought, and Woodstock Nation—a phrase coined by Abbie Hoffman (and the title of his 1969 book) to describe the idealistic youth of America in the 1960s who sought a better world—was nothing but a fantasy of spoiled, suburban kids, of wanna-be hippies. Even Brody’s choice of music was outdated. Brody was singing Dylan from 1967 but this was 1970. Music had moved on. Dylan had moved on. Hippies were outdated, having been, in Reitman’s words, “diluted, sterilized and absorbed.” Businessmen had long hair and sideburns and were wearing bell bottoms and paisley ties. Even Billy Graham was dressing in the mod-fashion. Vegas lounge singers sang rock medleys. The lingo of the counterculture—groovy, psychedelic, far out, etc.—had entered the general lexicon. Big business, fashion, TV, and Hollywood had all co-opted the hippie movement. Brody was, according to Reitman, nothing but “a product of the media.” “Michael Brody is what the Daily News thinks hippies are like.” He was “all the hippies rolled into one. He is a guitar-strumming child of wealth, yet he scorns the material existence to live on a chicken farm in Connecticut.”

Reitman thought that Brody was being used, by the record company executives looking to cash in on his fame, by TV newsmen looking for a story and by all the beggars who anxiously waited to see if they would be blessed with some of Brody’s bounty. Reitman was sympathetic. Brody “is not the villain of the story,” wrote Reitman. “The villains are the people who created him, the people who profit by him and the people who use him to get their rocks off, instead of doing it themselves. Michael Brody is Christ, a mental Christ, a crucified mind in a world where physical suffering is no longer anything unusual—and there are millions just like him.” Society, Reitman predicted, would discard Brody “like a used Kleenex.”

By the time Reitman’s article appeared, the world had, as he predicted, tossed Brody aside like used Kleenex, but Brody did not end up in some bar telling his sad story to the bartender. The months following Brody’s arrest were difficult. He ended up in a New York hospital for several days, either from a nervous breakdown or a drug overdose. After his release, the acute psychotic episodes recurred and he was hospitalized again and again. The drug possession charge was eventually dropped as it became clear that Brody’s hospitalizations would continue. Brody and Renée reconciled, separated, reconciled again. She spent more and more time at her parents’ house as her pregnancy entered the second trimester. Brody’s thoughts about Nixon and the War began to consume him. He no longer thought or spoke of loving or respecting Nixon, as he had done at the press conference following his attempted White House visit. Instead, his thoughts about Nixon focused on the President’s obstruction with his destiny to end the Vietnam War.

As Brody languished in treatment, a young Philadelphia doctor looking to buy a Corvette read about a 1968 Stingray for sale in upstate New York and arranged to look at it. A Scarsdale attorney was in charge of selling it for a client. The doctor liked the car. It was Daytona yellow with a hard top and leather seats. It handled well and had only a handful of miles on it. It was clean, except for the trunk, which was full of shopping bags filled with letters. The negotiation went smoothly. The price was right, and it was obvious the attorney wanted to sell the car. They quickly settled on a price, and the doctor signed the transaction papers not recognizing the name of the owner—Brody. The doctor made arrangements to get the vehicle back to Pennsylvania. A few days later, the Vette was trailered to Philadelphia. The doctor opened the trunk, and it was still full of unopened letters, all addressed to Brody and asking for money. The Vette had been sold to pay for Brody’s mounting medical and legal bills. Having given away his assets and with the next trust fund payment months away, Brody had started liquidating his remaining possessions.