•••

A Gluttonous and Hoggish Diet

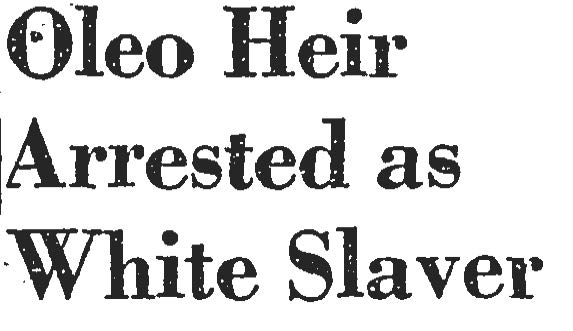

The first blow to Jack Jelke’s peaceful retirement occurred in August 1952 when his youngest child, Mickey, was arrested in New York City for running a high-class prostitution ring. His indictment followed, and the Jelke name was smeared in the headlines day after day as the press detailed the oily details of the prostitution ring. Mickey’s arrest was just the first in a series of misfortunes for the Jelke family.

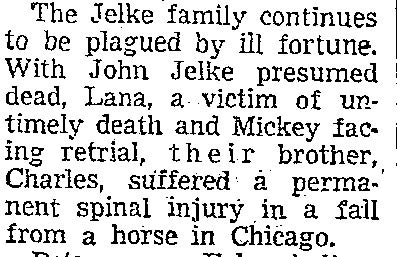

Two months after Mickey Jelke’s indictment, Lana Jelke Brody entered the hospital. She had been having trouble breathing and was running a fever. She had always been frail and sickly, suffering from rheumatic heart disease. She struggled after the birth of each of her children, particularly Michael’s. When she was admitted to the hospital suffering with pneumonia, her illness was duly noted by the gossip columnist Dorothy Kilgallen. She died on Friday, November 14, 1952, age 29. Her son, Michael, was four years old. His sister, Robin, was six.

Two months after Mickey Jelke’s indictment, Lana Jelke Brody entered the hospital. She had been having trouble breathing and was running a fever. She had always been frail and sickly, suffering from rheumatic heart disease. She struggled after the birth of each of her children, particularly Michael’s. When she was admitted to the hospital suffering with pneumonia, her illness was duly noted by the gossip columnist Dorothy Kilgallen. She died on Friday, November 14, 1952, age 29. Her son, Michael, was four years old. His sister, Robin, was six.

Five months after Mickey’s conviction, Frazier Jelke died, age 73. His estate would soon be valued at nearly $7,000,000, all of which was then placed into trusts for his son and three grandchildren. The estate assets did not reflect Frazier’s true net worth; in the years before his death, the assets had been carefully diminished to avoid taxes. Large sums were placed into his charitable foundation, and still other monies had been placed in other dynastic trusts for his son and grandchildren. Jack Jelke took his older brother’s death hard. Jack Jelke had been thinking about the family’s oleo fortune ever since he sold the family company to Lever Brothers. About a month after Frazier’s funeral, Jack Jelke sat down to write his will. He left sizable sums of money to his butler, personal secretary, cook and his two nurses. Various cousins received smaller bequests, as did his church. The “rest, residue and remainder” of his estate was placed equally into four separate trusts to benefit his three living children and his two grandchildren—Lana’s kids, Robin and Michael Brody. With death on his mind, Jack Jelke vowed to be closer to his children and grandchildren. But the bad luck continued.

Jack Jelke’s eldest son, Johnny, had been in Europe when Mickey was arrested. It was speculated that Johnny would be arrested as part of an expanded vice investigation. No charges were ever filed, and Johnny returned to New York. He was cautious and tried to keep a low profile. Johnny’s name was bandied about too much in Mickey’s trial—he had introduced Pat Ward to Mickey, and the nude photos that Mickey’s attorneys tried to use to discredit her may have been taken at Johnny’s apartment. Johnny supported his brother but kept his distance. He tried to spend as much time flying as possible. In January 1954, Johnny climbed into a P-51 for a routine Visual Flight Rule (VFR) training mission from White Plains, New York, to New Orleans, with re-fueling stops along the route in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Marietta, Georgia. On the ground at Dobbins Air Force base in Marietta, he asked that the tanks be topped off. From Dobbins, he would fly south/southwest to Mobile, then hug the Gulf Coast west to New Orleans, but Johnny had been given an inaccurate weather forecast from Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama, that led him to believe he could continue the VFR navigation instead of switching to instruments. He was also struggling with a weak radio compass.

Over Mobile, about 30 minutes from New Orleans, he radioed his altitude, 4,000 feet. The weather was bad: a storm had rolled in, shrouding the area in a thick fog. He asked whether he should continue the VFR navigation and drop to a lower altitude. The plane disappeared a few minutes later. A search by the Civil Air Patrol and various military planes failed to find any wreckage. Johnny was declared dead. His father was distraught, and spent over a $1,000,000 on private searches. He posted a reward for information leading to the location of his son’s body or the plane’s wreckage. Periodically, a fishing trawler plying the Gulf of Mexico would net a piece of an aircraft, and the owner of the boat would go to collect the reward, but the pieces of metal were always from different planes, different wrecks. For years after Johnny’s disappearance, some friends claimed he was on a secret mission for the government. Others—mostly girls Johnny had dated—asserted that he was alive and hiding out in Guatemala under an alias. The P-51 wreckage and Johnny’s body were never found.

Over Mobile, about 30 minutes from New Orleans, he radioed his altitude, 4,000 feet. The weather was bad: a storm had rolled in, shrouding the area in a thick fog. He asked whether he should continue the VFR navigation and drop to a lower altitude. The plane disappeared a few minutes later. A search by the Civil Air Patrol and various military planes failed to find any wreckage. Johnny was declared dead. His father was distraught, and spent over a $1,000,000 on private searches. He posted a reward for information leading to the location of his son’s body or the plane’s wreckage. Periodically, a fishing trawler plying the Gulf of Mexico would net a piece of an aircraft, and the owner of the boat would go to collect the reward, but the pieces of metal were always from different planes, different wrecks. For years after Johnny’s disappearance, some friends claimed he was on a secret mission for the government. Others—mostly girls Johnny had dated—asserted that he was alive and hiding out in Guatemala under an alias. The P-51 wreckage and Johnny’s body were never found.

The third Jelke boy, Chuck, also found that the family’s oleo money could not buy happiness. In 1952, just before Mickey’s arrest, Chuck Jelke had married Catherine Gerlach, better known by her nickname, Deeda. Seven-months later, Deeda gave birth to a little healthy girl, but the young couple gave her up for adoption for reasons that were unclear. Some thought that the young couple did not want a child to interfere with their lifestyle. Others questioned the child’s paternity. Two years after his marriage, Chuck was thrown from a horse and suffered a permanent spinal cord injury. His drinking increased as he struggled with the pain, and the marriage began to deteriorate. Deeda eventually sued for divorce in Illinois, claiming that he spent more time with his horses or the bottle than with her. She also alleged that, in the preceding years, he had “squandered, dissipated and scattered” $200,000 from various family trusts. Chuck countered by suing her for divorce in Florida. The papers carried the blow-by-blow of the jurisdictional fighting. She was eventually granted a divorce in Illinois on the grounds of desertion. Chuck drifted to West Palm Springs tending to his horses, drinking and running a charter boat concern with a World War II PT Boat that had been converted to a yacht cruiser.

The third Jelke boy, Chuck, also found that the family’s oleo money could not buy happiness. In 1952, just before Mickey’s arrest, Chuck Jelke had married Catherine Gerlach, better known by her nickname, Deeda. Seven-months later, Deeda gave birth to a little healthy girl, but the young couple gave her up for adoption for reasons that were unclear. Some thought that the young couple did not want a child to interfere with their lifestyle. Others questioned the child’s paternity. Two years after his marriage, Chuck was thrown from a horse and suffered a permanent spinal cord injury. His drinking increased as he struggled with the pain, and the marriage began to deteriorate. Deeda eventually sued for divorce in Illinois, claiming that he spent more time with his horses or the bottle than with her. She also alleged that, in the preceding years, he had “squandered, dissipated and scattered” $200,000 from various family trusts. Chuck countered by suing her for divorce in Florida. The papers carried the blow-by-blow of the jurisdictional fighting. She was eventually granted a divorce in Illinois on the grounds of desertion. Chuck drifted to West Palm Springs tending to his horses, drinking and running a charter boat concern with a World War II PT Boat that had been converted to a yacht cruiser.

Within a few short years, everything that Jack Jelke had worked all his life for unraveled. The appellate court’s reversal of Mickey Jelke’s conviction gave some hope, but Jack Jelke also suffered as he saw the Good Luck brand slowly disappear. Coinciding with Mickey Jelke’s second trial, in March 1955, Lever Brothers started marketing a new margarine at a price substantially higher than its Good Luck brand. Trying to show that the new margarine was luxurious, Lever Brothers called its product Imperial and used a crown as its symbol. As a further sign that it was an expensive product, Imperial was wrapped in aluminum foil. A year after Imperial was introduced in regional markets, Lever Brothers took the brand national. Imperial was the first margarine, as the ads promised, “unconditionally guaranteed to taste like the high-priced spread.” Lever Brothers said the recipe for Imperial was secret, and soon rumors circulated that it included a small amount of butter—for that special “butter” taste. Imperial sales quickly overtook Good Luck margarine.

Lever Brothers tinkered with Good Luck, increasing the size of the four-leaf clover on the package, focusing on its lightness and spreadability and wrapping its ¼ pound bars in two layers of aluminum foil—”double wrapped in aluminum to stay Fresher and Better Tasting than other margarine,” the ads said. Because some state laws still prevented the margarine companies from comparing their product to butter, Lever Brothers was forced to write ads that said Good Luck margarine was “more nourishing than ‘you-know-what’” or “a spread you can’t tell from ‘you-know-what.’” There were other angles and other advertising campaigns. Lever Brothers changed the formula and manufacturing technique for Good Luck. It introduced an economy “family size” carton, which saved 2 cents per pound. It offered to sell butter knives, at a nominal sum, when a consumer returned the labels from two packages of Good Luck. It ran contests that were designed to benefit the paper delivery boys—offering college scholarships or gifts for those who collected and redeemed labels from Good Luck margarine packages. It changed the packaging at least three times, each designed to emphasize the four leaf clover or the foil wrapping. Sales increased with each change, only for a short time. Overall, sales of Good Luck remained flatter than the projections. Lever Brothers’ other margarine, Imperial, remained strong in the market: its higher quality package sold at a higher price but also sold better than the lesser priced brands, like Good Luck. America in the 1950s was a growing country, and one where excess was the norm.

Lever Brothers tinkered with Good Luck, increasing the size of the four-leaf clover on the package, focusing on its lightness and spreadability and wrapping its ¼ pound bars in two layers of aluminum foil—”double wrapped in aluminum to stay Fresher and Better Tasting than other margarine,” the ads said. Because some state laws still prevented the margarine companies from comparing their product to butter, Lever Brothers was forced to write ads that said Good Luck margarine was “more nourishing than ‘you-know-what’” or “a spread you can’t tell from ‘you-know-what.’” There were other angles and other advertising campaigns. Lever Brothers changed the formula and manufacturing technique for Good Luck. It introduced an economy “family size” carton, which saved 2 cents per pound. It offered to sell butter knives, at a nominal sum, when a consumer returned the labels from two packages of Good Luck. It ran contests that were designed to benefit the paper delivery boys—offering college scholarships or gifts for those who collected and redeemed labels from Good Luck margarine packages. It changed the packaging at least three times, each designed to emphasize the four leaf clover or the foil wrapping. Sales increased with each change, only for a short time. Overall, sales of Good Luck remained flatter than the projections. Lever Brothers’ other margarine, Imperial, remained strong in the market: its higher quality package sold at a higher price but also sold better than the lesser priced brands, like Good Luck. America in the 1950s was a growing country, and one where excess was the norm.

Margarine was part of the great expansion of America. John F. Jelke’s belief that there was a vast market for yellow margarine had proven true. In 1909, the average American ate 17.90 pounds of butter per year but only 1.20 pounds of margarine. In 1949—the year after The John F. Jelke Company was sold to Lever Brothers—the average American ate 5.70 pounds of margarine per year, about half of the amount he consumed of butter. After the Margarine Act of 1950 removed the obstacles to selling colored margarine, yearly per capita consumption of margarine steadily increased. By 1958, the average American ate more margarine per year than butter. But the consumption of margarine was also tied to the expansion of the American waist size and associated problems.

The newspapers started publishing stories of the studies in 1956. “Doctor Blames Hoggish Diet for High Heart Disease Toll,” one newspaper headline read. America’s “gluttonous and hoggish diet” was resulting in a mounting death rate. The problem was excessive fat, particularly the hard, or saturated, fat, in the American diet. The excessive fat was clogging arteries in the heart and the brain. For years, studies had connected excessive fat with heart disease. It had been assumed that bad fats had an animal ancestry while good fats were vegetable based. In the mid-1950s, however, research showed that vegetable-based fats, if hydrogenated, were no better than animal-based saturated facts. But the escalating death rate was also associated with another aspect of America—the disease of keeping up with the Joneses. One doctor explained the connection between the competitive lifestyle and coronary heart disease: “Emotional tensions developed in the race for bigger cars and finer fur coats may also be involved.” With President Eisenhower’s heart attack in September 1955 ingrained in the public’s mind, the American consumer was apt to pay attention to warnings about diet and lifestyle (at least temporarily).

In the gluttony of America, companies saw opportunity. In 1958, The Pitman Moore Drug Company introduced Emdee, a margarine made with non-hydrogenated corn oil and rich in linoleic acid, which supposedly had a cholesterol-lowering effect. Sales of Emdee were restricted because it could be purchased only in drug stores. The margarine industry quickly moved to put similar products on the grocery shelf for the diet-conscious consumer. Mrs. Filbert’s Margarine led the charge, explaining that it was made with “the finest domestic oils, which contain no cholesterol” and that the “oils, partially hydrogenated for texture, remain over 80% unsaturated.” With added Vitamins A and D, and a low salt content, Mrs. Filbert’s was “for good eating…and good health!” Other companies followed.

The Corn Products Company, makers of Nucoa margarine, decided to introduce a 100% corn oil margarine: Mazola was marketed as being low in saturated fats because it used liquid corn oil in a manufacturing process that the Corn Products Company had patented. Soon, the formula for Nucoa was also changed to incorporate liquid corn oil. Another leading maker, Standard Brands, Inc., introduced Fleischmann’s Sweet Margarine, which, like Mazola and Nucoa, featured the use of liquid oils, primarily corn. The process for these new margarines had actually been developed in 1938 by The John F. Jelke Company. Even though The John F. Jelke Company had developed the process for reducing saturated fats in margarine, Lever Brothers was slow to exploit the health concerns over saturated fats. While Mazola and other corn-oil based margarines were able to secure a market share with aggressive advertising in the late 1950s and early 1960s it would be several years before Lever Brothers began to advertise Good Luck’s “preferred unsaturates…and preferred flavor…at no extra cost.”

Part of the reason Lever Brothers was slow to react was its preference for Imperial margarine, which was clearly its flagship product. Good Luck was by the late 1950s considered a secondary brand. Sales of Good Luck stagnated as other companies exploited their “new” margarines and “new” formulas or processing methods. The history of Good Luck was working against it. It had been around for so long that many Americans, particularly those influenced by the health concerns over saturated facts, viewed Good Luck as being made with beef suet, even though that practice had ended a half-century earlier. Other factors also affected sales of Good Luck. The retooling of the Good Luck brand, with the four leaf clover as a trade symbol instead of the little Dutch girl, never caught on. While Lever Brothers’ removal of “Jelke” from the name may have helped in the immediate aftermath of Mickey’s trials, ultimately that excision lost much of the good will that The John F. Jelke Company had developed. To the public, the name Jelke meant margarine, just as Mrs. Filbert’s and Fleischmann’s meant margarine.

In 1959, Lever Brothers tried to breathe life into the old brand with a radical television and radio advertising campaign. Eleanor Roosevelt, the 74-year-old widow of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was looking for a way to speak to the American public about important world matters. Thirteen years earlier, President Truman had appointed her a delegate to the fledgling United Nations, where she was involved in drafting the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She later served as the chair of the first UN Human Rights Commission. There was a certain duty that came with wealth—it was often called noblesse oblige. Her husband, a man elected to the presidency four times, had it. He was, according to the title of a recent book, a traitor to his class because he wanted to help and protect the downtrodden, the out of work, the misfortunate, the oppressed. And Eleanor shared that vision. She had found a voice with the United Nations, and, more than that, she found an awareness of the world. America’s triumph in World War II had ushered in a new era, where, she hoped, the United States would use its position of power to help the less fortunate. In the post-War years, Mrs. Roosevelt became an American icon. She traveled, continued to write her newspaper column (“My Day”) and had a weekly radio show and a Sunday television show. Some national political figures thought that she should be nominated to run as Harry Truman’s vice-president in 1948. She routinely topped the annual lists of most admired and respected women. She lectured on human rights and the role of the United States in the world. More and more, she had become aware of America’s wealth and, more importantly, the hunger and poverty in many countries. As the 1950s aged, she also became more and more concerned about the conspicuous consumption—one might say, the “gluttonous and hoggish diet”—of the American consumer and way of life.

In 1959, Lever Brothers tried to breathe life into the old brand with a radical television and radio advertising campaign. Eleanor Roosevelt, the 74-year-old widow of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was looking for a way to speak to the American public about important world matters. Thirteen years earlier, President Truman had appointed her a delegate to the fledgling United Nations, where she was involved in drafting the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She later served as the chair of the first UN Human Rights Commission. There was a certain duty that came with wealth—it was often called noblesse oblige. Her husband, a man elected to the presidency four times, had it. He was, according to the title of a recent book, a traitor to his class because he wanted to help and protect the downtrodden, the out of work, the misfortunate, the oppressed. And Eleanor shared that vision. She had found a voice with the United Nations, and, more than that, she found an awareness of the world. America’s triumph in World War II had ushered in a new era, where, she hoped, the United States would use its position of power to help the less fortunate. In the post-War years, Mrs. Roosevelt became an American icon. She traveled, continued to write her newspaper column (“My Day”) and had a weekly radio show and a Sunday television show. Some national political figures thought that she should be nominated to run as Harry Truman’s vice-president in 1948. She routinely topped the annual lists of most admired and respected women. She lectured on human rights and the role of the United States in the world. More and more, she had become aware of America’s wealth and, more importantly, the hunger and poverty in many countries. As the 1950s aged, she also became more and more concerned about the conspicuous consumption—one might say, the “gluttonous and hoggish diet”—of the American consumer and way of life.

Soon after the new year, Lever Brothers approached Mrs. Roosevelt about becoming a spokesperson for Good Luck margarine. First Ladies and ex-First Ladies did not pitch products, but Mrs. Roosevelt agreed and recorded three television commercials and several radio spots. The money she received from Lever Brothers, reported to be $35,000, went to one of her charities, and each of the commercials was made with a public service message designed to help the poor of the world. With Mrs. Roosevelt seated at a dining room table, the announcer intoned: “Ladies and Gentlemen, Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt.” Mrs. Roosevelt, attired in a black dress, looked right into the camera. A cup and saucer sat on the table, and she held with her left hand a piece of toast, lathered with a lovely spread of melting margarine.

“When you sit down to breakfast, don’t you often think of the starving people of the world?” she asked. “I wish we could share our abundance with them.” She spoke of America’s wealth, its crops and food. She said that two-thirds of the world was underfed. She hoped that America would share its wealth and food with the world, including “wholesome foods like Good Luck Margarine.” She added, in her New York Brahmin accent: “Years ago most people never dreamed of eating margarine but times have changed. Nowadays you can get a margarine like the new Good Luck, which really tastes delicious. That’s what I have spread on my toast. Good Luck! I have thoroughly enjoyed it!” The camera panned out, slightly, with the announcer’s close: “The margarine Mrs. Roosevelt has just recommended is new Good Luck, the light margarine. Good Luck is light in flavor, light on your tongue and leaves no oily after taste.”

The first television commercial ran on February 16, 1959, on NBC during “Haggis Baggis,” an afternoon quiz show where contestants, usually housewives, tried to identify a celebrity whose photograph was hidden behind a grid of quiz categories. With each correct answer, a portion of the photo would be revealed: the first contestant to identify the celebrity won. The spot was re-played on various daytime television shows sponsored by Good Luck margarine on the NBC network, mostly game shows that catered to housewives but also on re-runs of “I Love Lucy,” another show with a primarily female audience. The radio ads followed the same theme. Response to Mrs. Roosevelt’s pitching oleo was mixed.

Jack Gould, longtime television critic with the New York Times, thought that “the sight of her raising her eyes to the camera and linking her concern for the world’s needy with the sale of a food product at the retail counter was disquieting in the extreme.” Other writers viewed the commercials a “lapse in judgment,” a “mistake” or the “booboo of the year.” Mrs. Roosevelt shrugged off the criticism. She held a press conference. The commercials, she said, were a necessary step to inform Americans of the plight of the world. She had been trying to persuade a network to allow her to go on the air with a regular show where she would discuss the needy of the world–the poor, the underfed, the victims of oppression. She wanted a venue to “repeat over and over again some of the things that I think are important for our people to hear,” but she had no takers. She was told that the message was too controversial. Lever Brothers was willing to allow her a few seconds, and she seized the opportunity. “If the commercials were successful,” she explained a few days after the first one aired, “I felt they might lead to an opportunity for a real program. In these there commercials I managed to get across the news that thousands of the people of the world are hungry and that we have an abundance of food we could share. One can get across by television and radio to millions of people. And one can travel indefinitely and reach only a few thousand. I felt that this was the best way to reach people.”

The television and radio spots by Mrs. Roosevelt boosted Good Luck sales for a brief time, but it was clear the brand was dying. When Mrs. Roosevelt first appeared on television to sell Good Luck margarine in 1959, Jack Jelke was contemplating what to do with his oleomargarine fortune. The oleo fortune that he had built—that his father and grandfather had built—weighed heavily on his mind. At times, it all seemed a waste—the long hours spent at the margarine plant overseeing the manufacturing process or on the road hawking Good Luck oleo. It had cost him his marriage. His only daughter, Lana, had died young, leaving two small children motherless. His eldest son, Johnny, had disappeared and was presumed dead. Chuck, the next in line, was divorced and quickly becoming a drunk. Mickey was out of prison but also headed for divorce. Jack Jelke wanted to do something good with his oleo money, and so in December 1959, he donated $1,000,000 to St. Luke’s Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago to construct the Jelke Memorial Building.

Jack Jelke was 72-years old when the bequest was announced. He had finally stopped following the travails of Good Luck margarine. For the most part, he stayed in his mansion in Lake Forest, Illinois. He enjoyed reading history books. He played a little golf or bridge at the nearby Onwentsia Club, and he kept busy as an active member of a number of Chicago civic organizations—the Chicago Historical Society, the Chicago Art Institute and the Chicago Museum of Natural History. He frequently went downtown to the Chicago Club, where he found refuge among the movers and shakers of the business world. Jelke had seen, and read, enough headlines about his family over the years, and The Chicago Club’s rule forbidding the entry of any working member of the press was to his liking.